ISABEL’S STORY

It is daunting to try and capture our little girl, what she means to us, and the circumstances we face, in just a few paragraphs, but here goes. Isabel Evelyn Cowan was born on January 19, 2014. We were the parents that had the nursery painted, picture frames hung just so, and baby library stocked with all the classics. Isabel was not just our first born, but the first grandchild on both sides of our very excited family. Isabel’s birth was without complication, her length, weight, head circumference, and other features grossly normal, and we took her home from the hospital to begin our lives as a little family together. Looking back on her baby pictures now, with her big round eyes, full but delicate swirls and wisps of hair, with dimpled tiny fat fists, we wonder - how is one supposed to know? For although Isabel looked like everyone’s idea of a healthy baby girl, we would learn only a few years later she suffers from a life-limiting condition.

Isabel grew in those first few months as we expected her to, reaching some of the first development milestones timely. It wasn’t until all her same-age peers were able to sit unassisted much earlier than Isabel that we began to wonder, but then again, each child is unique, right? Isabel was generally happy and otherwise seemed fine day to day, so we continued on, trying not to let our fears stand in the way of soaking up all the joy she brought us. Try as we did, however, we had a gut feeling that there may be something more deeply impacting her health.

When Isabel was 14 months old, after some more missed milestones, we undertook a series of evaluations with pediatricians and therapists, in search of some answers. We remember wanting desperately for the specialists to shoo us away, to say we’re crazy, and that Isabel would catch up in due time. While the feedback was mixed as to how concerned we should be at that point, no one shooed us away, and a new term came creeping into our lexicon: global developmental delay.

This was a catch-all term assigned to Isabel, as a nearly 1.5 year old child who was not walking, talking or demonstrating other skills near where her typically developing peers were, with no known explanation. Isabel qualified for early intervention and this period kicked off a series of therapies (physical, speech, occupation) that have come to shape Isabel’s weekly routine and remain with us to this day. The testing continued, including blood work, EEGs, MRIs, overnight stays at the hospital, and genetic testing.

Our network of doctors soon grew from our pediatric group in Pasadena, California, to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and beyond. Through every test, all the hand wringing, fasting, fears and tears, Isabel braved through it all with a spirit and resiliency that moved and encouraged us. The tests during this year came back generally inconclusive, and we were given little more than the global development delay description. It was deflating in every way. Our heart ached for months. Despite being surrounded by friends and family, we felt profoundly isolated. One glimpse of light during this otherwise dark period came in February 2016, when, after what had been nearly a year of physical therapy, Isabel took her first steps, at 2 years old. She had worked so hard to achieve that milestone and we were elated for her.

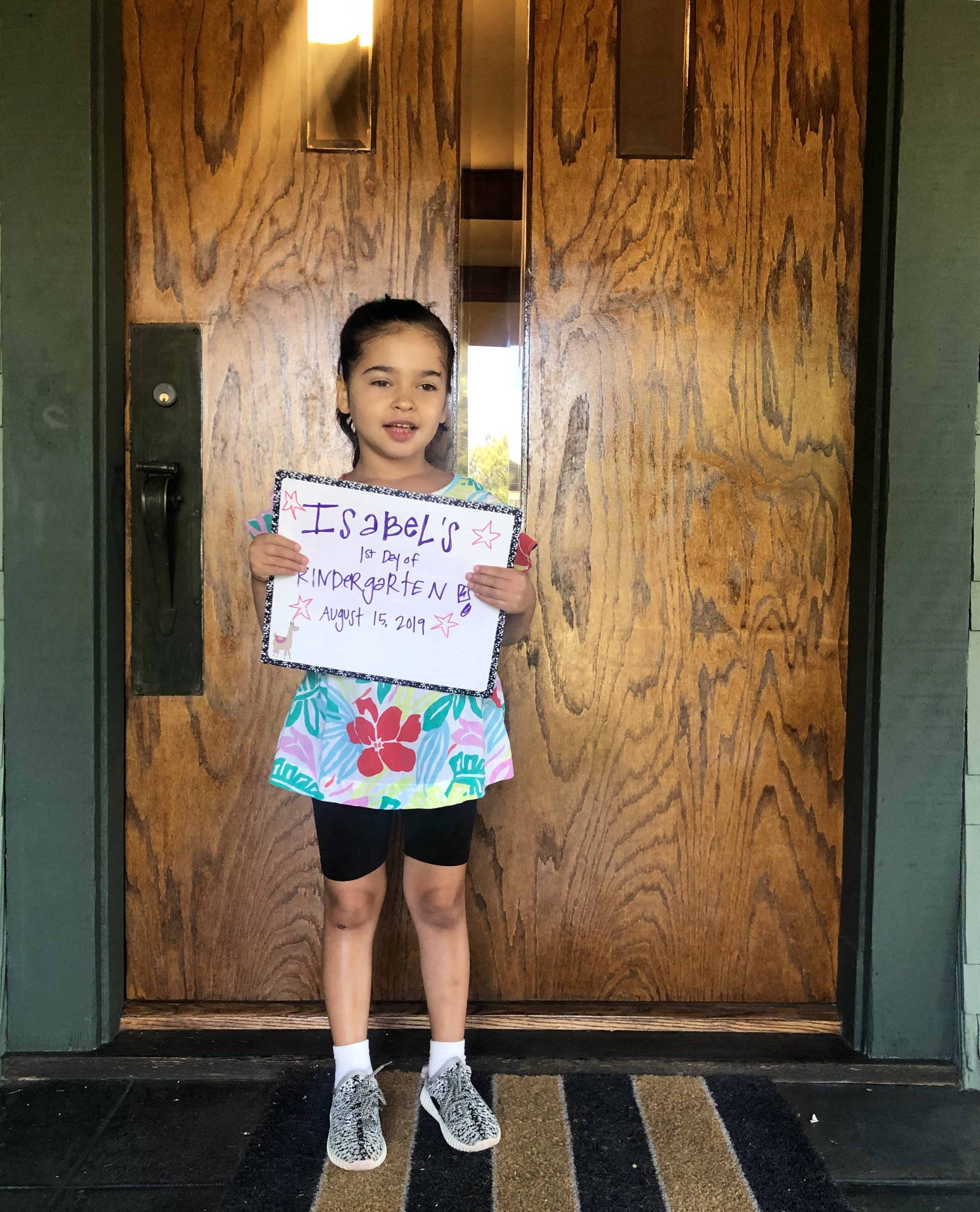

Isabel soon came of school age, and with that came the struggle to get her adequate support and the free and appropriate public education to which she is entitled within the local school system. We placed Isabel in a special education class, but every accommodation and service, from class placement to therapies had to be painfully extracted from our disorganized and uninterested school district. They even went so far as to try and withhold the services to which we had a legal right because Isabel had no formal diagnosis. We eventually made the decision to move one town over, to a school district that has been fantastic and made a tremendous difference for Isabel and our family.

In October of 2019 we transitioned care to a neurologist at CHLA who took a specific interest in Isabel’s condition and refocused our efforts back to genetic testing, with a more targeted approach. During this time, with the help of our passionate neurologist and the medical professionals at CHLA, we made inroads to treating some of Isabel’s symptoms, including through the use of seizure medication to alleviate abnormal, seizure- like neural activity, and natural and medicinal sleep aids to help Isabel establish and maintain more regular sleep patterns (kiddos with her condition are often up and awake every 2 hours each night, disrupting autophagy cycles, inhibiting the body’s natural mechanism for regenerating and regrowing itself).

Thursday, November 14, 2019 is a day neither of us will ever forget. After the prior round of genetic testing (including panels for Angelman’s Syndrome, which we studied and suggested to CHLA be tested, due to similarities in profile) yielded no conclusive results, we received an email that our test results were in and should be discussed. That day we learned from a geneticist Isabel suffers from a spontaneous mutation on her WDR45 gene, which is linked to an ultra-rare genetic disease - Beta-propeller associated Neurodegeneration (or BPAN).

Not only was this condition not curable, but it would get worse. We were numb. We knew so little about BPAN and spent the next several months grieving, but also immersing ourselves in everything we could find online, from complex scientific journals, to social media groups, to the few nonprofit organizations with information on BPAN and the other Neurodegeneration with Brain Iron Accumulation diseases. We learned that as a disease impacting only a few thousand people (and not hundreds of thousands or millions) worldwide, it is considered an orphan disease and that there are very few doctors aware of, let alone trained in, managing the disease. We discovered that few very private and public research institutions were dedicating resources to developing treatment and therapeutics. Worst of all, we came to understand that those children afflicted with BPAN experience Parkinsonism and physical and mental decline in early adolescence. We had our answer and something more specific than global developmental delay, but time is going to run out on us. We have to do something. One of the most precious things in this world to us, our little girl, may be taken from us far too early. AND THIS IS WHY WE’RE HERE.